By Matthew Holloway |

The University of Arizona’s (UA) newly implemented civics requirement, adopted under an Arizona Board of Regents (ABOR) mandate, is intended to ensure every graduate receives instruction in American government and constitutional principles. But critics warn the university’s rushed structure may undermine the very purpose of the reform.

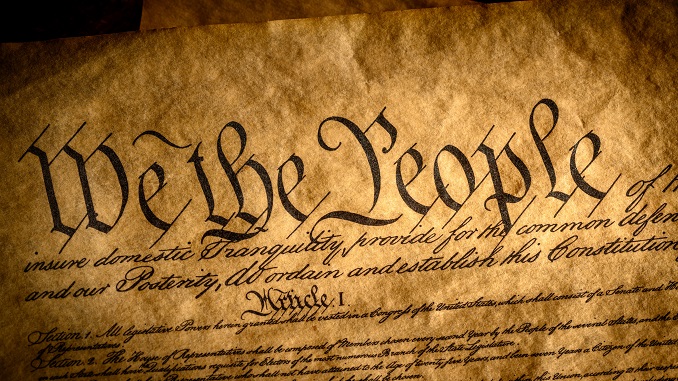

Under the proposed plan, UA students will fulfill the entire ABOR civics mandate through a single three-credit general education course. As mandated by the ABOR policy, the curriculum requires instruction in seven areas “at a minimum,” including U.S. history’s impact on the present, core principles of constitutional democracy, our major founding documents, landmark Supreme Court cases, practical civic participation, and basic economic literacy, material that peer institutions typically divide across multiple courses.

Mark Stegeman, an associate professor of economics at the University of Arizona and longtime member of the university-wide General Education Committee (UWGEC), recently described the policy proposal as “a car crash in the making” in an op-ed for the Tucson Sentinel. Stegeman cited both academic and procedural concerns with the program’s development and execution.

Stegeman noted that a former UWGEC chair admitted the committee was “just throwing stuff against the wall” during a previous breakneck approval process. He added that at the last meeting of the committee, no one present could answer his questions about seat capacity and course availability by spring 2027. He asked whether UA can reliably offer enough sections of the new civics course to accommodate all graduating students without creating scheduling bottlenecks that delay completion.

He warned that “thousands of students arriving in nine months will face a graduation requirement” built on courses that do not yet exist, with no completed development, approval process, or clear seat-capacity plan.

Those logistical concerns amplify the academic ones. Should the course become oversubscribed or rushed through, the civics requirement could devolve into a mere procedural hurdle rather than a meaningful educational foundation.

The Board of Regents’ directive was designed to restore structured instruction in American institutions across Arizona’s public universities. Other state universities interpreted the requirement differently. Arizona State University requires students to complete both an American institutions course and a civic engagement-focused course. Northern Arizona University has also implemented a two-course model.

As Stegeman summarized: “ABOR’s Civics mandate spans history, economics, landmark Supreme Cases and constitutional debates, information literacy, opportunities to practice civil disagreement and civic engagement, etc. Neither ASU nor NAU attempt to squeeze it all into a single 3-unit course, which would be nearly impossible to do well. UA’s proposal simply omits most of it.”

Beyond the academic criticism, Stegeman raised concerns about how the program was developed internally. According to his analysis, key committees lacked clear structure and broad representation, with significant influence coming from administrative offices rather than a balanced cross-section of departments.

At a time when national surveys consistently show declining civic knowledge among younger Americans, fewer than a third can name most of the First Amendment rights, and only 7% can name all five, according to Annenberg’s 2024 survey.

Many critics among the media and online have argued that universities should expand, not compress, serious instruction in American government.

In March, Fox News’ Jesse Watters shared a segment in which beachgoers in Fort Myers, Florida, failed basic American civics questions alarmingly, including naming the first President of the United States, the three branches of government, and the number of Supreme Court Justices.

In an August 2024 report on youth civics, News21 and the Associated Press noted that in the 2022 midterm elections, only about 1 in 10 voters nationwide was between 18 and 29, according to the Pew Research Center. A June Marist survey found that about 67% of registered Gen Z and Millennial voters said they intended to vote in 2024—compared with 94% of Baby Boomers. After the election, Tufts University’s CIRCLE program estimated that roughly 47% of young people ages 18–29 actually cast ballots in 2024, based on aggregated voter-file data from 40 states. Together, those numbers suggest a generation that is sizable, but still underrepresented and underprepared in the electorate.

When civic education is treated as a matter of efficiency rather than formation, the result can be accurately termed credentialed ignorance: students who pass a requirement but leave without the depth of understanding it was designed—and indeed legally mandated—to provide. The Board of Regents’ civics mandate was supposed to rebuild civic education with rigor and seriousness. Critics like Stegeman argue that UA’s one-course model risks missing that opportunity by prioritizing speed and administrative simplicity over depth.

Matthew Holloway is a senior reporter for AZ Free News. Follow him on X for his latest stories, or email tips to Matthew@azfreenews.com.