By Arman Sidhu |

Just two years after voters approved a $161 million bond in 2023, the Kyrene Elementary School District has unveiled a deeply unpopular, albeit long overdue, austerity plan to shutter nine of its 25 schools. Final decisions on which campuses will close remain in flux until December.

This should alarm not only Kyrene residents but also taxpayers in neighboring East Valley districts such as Chandler, Gilbert, and Mesa, which have likewise postponed needed consolidations despite data showing the urgency for school districts to “rightsize” to avoid future financial shocks.

Kyrene’s predicament shows what happens when district leaders, aided by special-interest boosters, ignore demographic realities and lean too heavily on bonds and overrides to prop up aging, half-empty facilities. Beyond the loss of schools and public trust, Kyrene’s crisis is a cautionary case study in how long districts can keep kicking the can on closures and restructuring before the math catches up.

For decades Kyrene ESD has fiercely defended its autonomy, resisting consolidation with Tempe Elementary School District, most notably in 2008, when Tempe voters approved a merger that Kyrene voters rejected by a 2-to-1 margin. The district has also resisted unifying with Tempe Union High School District, which serves most Tempe and Kyrene graduates. The result: three separate, duplicative bureaucracies servicing the same boundary zones of attendance.

That independence once seemed justified. By the 1980s and 1990s, Kyrene’s fortunes soared with population growth and rising property values following Phoenix’s annexation of Ahwatukee. A building boom beginning in the 1970s relieved Kyrene’s historic reliance on drawing students from outside its boundaries. That same appetite in housing translated to Kyrene’s expansion of schools, fueled by voter-approved bonds and overrides. Like many East Valley districts, Kyrene’s bond and override measures have passed easily, and typically without organized opposition.

Those glory days are long gone. Enrollment has fallen from 20,000 students in 2001 to roughly 12,000 today. That represents a 40 percent drop while the district continues operating 26 schools, a daunting figure considering it only serves grades K-8. Demographers project another 1,000-student decline within five years, equating to roughly $7 million less in state funding. Eight Kyrene campuses are less than half full, and three others are barely above that mark, culminating in the present restructuring effort.

Although Kyrene does have an override measure on the ballot for 2025, it remains to be seen if the drastic restructuring plan will have any impact on voter sentiment in the area for future bond requests. Given that Kyrene has spent millions from the recent bond request on schools now marked for closure, governing board members would be hard-pressed to make their case to residents for additional funding. Taxpayers who were told in 2023 by Superintendent Laura Toenjes that the bond would be “one more example of Kyrene’s commitment to fiscal responsibility” are right to demand answers about the gap between two decades of declining enrollment and the district’s continued inaction.

Kyrene is hardly alone. Large systems such as Chandler Unified remain locked in a perpetual bond-and-override cycle, masking structural enrollment declines with new debt and vague promises of an enrollment recovery effort that grows less plausible each year.

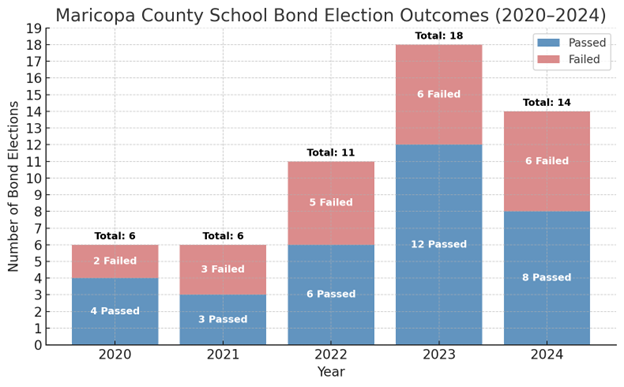

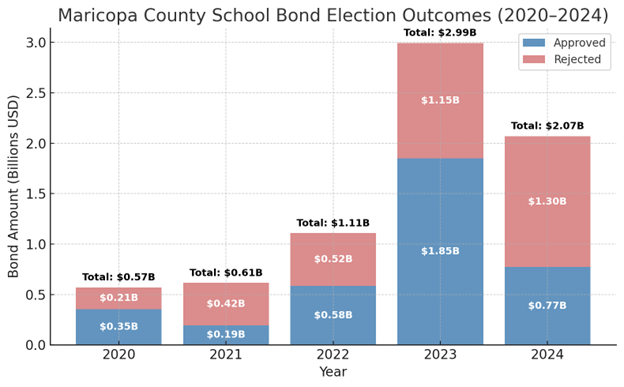

As seen in the chart below between 2020 and 2024, bond requests across Maricopa County have ballooned as pandemic stimulus dollars expired and districts turned back to property-tax financing. The pace of school bond elections far exceeds municipal ones, and the total amounts sought have surged as seen in the 2nd chart below. Inflation alone doesn’t explain the escalation, though it is often erroneously cited as the root cause of this growth.

The lesson isn’t that districts should never seek voter support, but that leaders must confront an uncomfortable truth: demand for traditional district schools is shrinking. Some causes, like rising housing costs and lower birth rates, are beyond their control. Others, like families choosing charters or ESAs, are the direct result of competition and consumer preference. Pretending otherwise guarantees more sudden, painful closures down the road, along with wasted opportunities adding up to hundreds of millions in taxpayer funds.

Kyrene’s crisis is neither the first nor the last domino of overbuilt school districts. Every district that keeps chasing bonds to prop up half-empty schools is writing the same ending. The can has been kicked far enough. It’s time to stop borrowing from tomorrow to preserve yesterday’s mistakes.

Arman Sidhu is a lifelong Arizona resident and educator who has served as a teacher and principal in both traditional public and charter schools. He is a doctoral student in education at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. His opinions are entirely his own.